Throughout this blog, examination of Illich’s (1976) theory will take place by studying ‘medical imperialism’ and bringing in the idea of ‘Iatrogenesis’. Through the main theme of medicalisation, we aim to investigate what the theory involves and how it has affected views on medicine. Also, the focus will be upon opposing theories that argue the intervention of medicine is sometimes welcoming and which challenge these ideas by bringing in other social agents. The posts within this blog will consider Illich’s (1976) ‘medical imperialism’ through different case studies which will highlight the relevance of this theory today.

Medicalisation is defined as when a “non-medical problem become defined and treated as medical problems, usually in terms of illness and disorders” (Conrad, 2007: 4), it is predominantly argued that deviant behaviour is transformed and manipulated into medical terms, creating a pathway for the occurrence of this process of medicalisation (Furedi, 2008) . It has profoundly increased in the modern, industrialised world (Shilling, 2003) alongside the shift in dominant social institutions where scientific/medical beliefs have overpowered religion (Rosner, 2001). This has encouraged social control of the medical establishment over the individual and their bodies, alongside other social institutions increasingly encouraging this such as the media (Conrad, 2007). Conrad and Schneider (1992) state that this can happen in a five-stage process. The first stage is defining a behaviour as deviant before a medical profession defines it (Conrad and Schneider, 1992). The second stage occurs when a medical professional discovers and recognises the problem, leading to a third stage where the medical and non-medical interests unite to seek for further research into illnesses (Conrad and Schneider, 1992). This then leads to the legitimisation of medical turf for the illnesses, which is stage four (Conrad and Schneider, 1992). The final stage of medicalisation is when the deviant problem becomes institutionalised and therefore becomes a wider social problem (Conrad and Schneider, 1992). This idea therefore shows how a non-medical problem can be medicalised, however it must be noted that not every problem is fully medicalised, so this model cannot always be used to explain how a problem or deviant behaviour may be medicalised (Gabe, Bury and Elston, 2004).

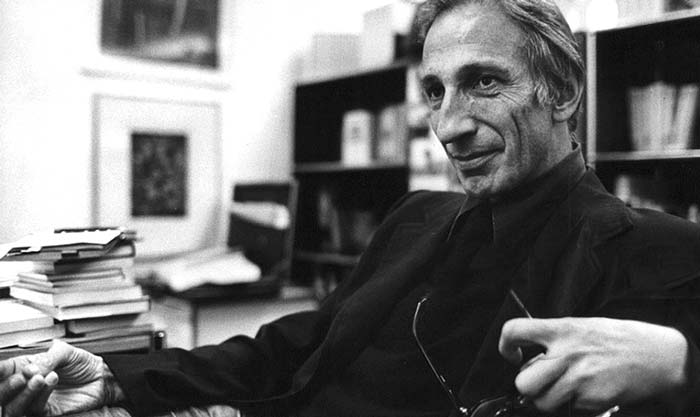

Negatively associated with medicalisation is Illich’s (1976) critical view of societies’ dependence on the medical profession/ the use of medical care and particularly the control the medical establishment have on society because of this (Conrad, 2007). This forms the argument that through modernity and industrialisation, heavy bureaucratisation of the medical profession has developed (Ballard and Elston, 2005) which leads onto his theory of medical imperialism (Gabe et al, 2004). This is where Illich (1976) claimed that the medical establishment predominantly assert excessive control over the lay population and convince the public of medical professionals’ ‘superior’ knowledge and skills (Lupton, 1994). Therefore, the notion of medical imperialism shapes the medical field as a phenomenon of control over society, alongside other critics who also link the growing issue of medicalisation to social control (Conrad, 2007). Zola (1972) further notes that medicines control over society has occurred and expanded over time (Williams, 2003) and also blames developments in finances and technology (Moynihan and Cassels, 2005). Due to these contemporary medical advances, medical professionals are gaining access to individuals’ lives and therefore intruding on issues originally known as social issues such as men’s physique (Gill et al, 2005) which will be discussed further in the ‘men at risk’ blog entry. He further argued that due to the increase in medicine and technology a dependency culture has been born and an individual’s responsibility has been removed (Illich, 1976). However, there is reluctance when it comes to medical imperialism, as it is not just the individual who is involved in the growing medical authority, outside influences, such as private health, or government inputs can have an ever growing effect on how the medical authority is extending its reach beyond doctor-patient relationship (Williams, 2003).

Further, it is evident that much theory proclaims the medical establishment is becoming a major threat to patients’ health (Williams, 2003). Illich terms this Iatrogenesis, claiming that “the medical profession is extremely damaging in itself to both individual and society” (Morrall, 2009:122), this is seen through doctor-inflicted injuries and the dependence of the medical establishment on individual bodies (Bradby, 2009). This is then developed into three categories; producing harm at a clinical level includes ineffective treatments and side effects, the social level includes the population producing an artificial need for pharmaceutical products (Williams, 2003; Ballard and Elston, 2005) and finally, the structural level demonstrates individuals losing capability to care for their own bodies, and the responsibility of health is placed on the medical establishment (Williams, 2003). This theory claims that negative side-effects predominantly outweigh any positive benefits where medicine is concerned (Ballard and Elston, 2005). The evidently heavy dependence seen from lay-patients is highlighted throughout both theories of medical imperialism and Iatrogenesis but more contemporary theorists argue it should not be assumed that the patient population are passive in this process as contemporary society has led to higher volumes of medical knowledge through many social advances (Van Dijk et al, 2016; Williams and Popay, 2006).

Through contemporary advances in technology, there is confirmation that there are many more social actors/institutions besides medical professionals creating this dependence, including the media and pharmaceutical companies (Van Dijk et al, 2016). It is usually the media that is at the forefront of pharmaceutical companies’ goals to achieve dependency on medical products (Kimmel, 2005), increasingly done through aspects of disease mongering, creating illnesses by making mild symptoms into major concerns and promoting this to the public (Moynihan and Henry, 2006). As these institutions develop in the medical industry, medical professionals’ authority seems to be in decline.Over time, according to Jewson’s (1976) medical cosmology, laboratory medicine has overtook bedside and hospital medicine as the dominant paradigm, this loses individual patient identity and focuses more on the causes of disease in a laboratory environment (Armstrong, 1995). Through this social shift in medicine, doctors especially have distanced themselves from patients, depersonalising the doctor-patient relationship and often decreasing the power of the medical professional (Calnan, 1984). This results in doctors/medical professionals being less involved in the medicalisation process (Fainzang, 2013), which is often referred to as de-professionalisation, not only because of this distancing doctor-patient relationship, but because the gap of medical knowledge between the two groups is constantly being reduced (Gabe et al, 2006). These decreasing gaps are evident when focusing on self-medication, where it is mostly the patient who instigates the process of medicalisation and increasingly do not feel they need to include a doctor within the process as their knowledge is adequate enough (Fainzang, 2013). A counter argument is then apparent against Illich’s theories – if doctors are becoming less involved in the process of medicalisation and patients are becoming more knowledgeable, then theories such as medical imperialism and Iatrogenesis are surely less significant. Advances in technology have been crucially important in the expansion of medical knowledge amongst patients, especially the internet where anyone has easy access to medical knowledge in this ‘over-developed world’ (Bradby, 2012). Parens (2011) states that technological advancements have been embraced by scientists and lay-patients who are very critical of the idea of medicine overtaking the bodies. This is due to the notion of technology allowing women to control their bodies through medical technological, such as birth control pills, vasectomies and abortion, which is often praised by feminists (Parens, 2011).

Parsons (1975) argues that medicalisation is not always negative, but valuable for people with illnesses. Medicalisation developed the notion of ‘sick role’, defining as “ill individuals exempted or excluded from normal role responsibilities, will seek out and cooperate with medical help, be exempted from blame for their condition and, will wish to get better” (Crossley and Crossley, 1998: 158). The ‘sick role’ notion teaches the individuals to conform to societal norms and values surrounding sickness, to deter the ‘deviant’ label (Parsons, 1975). Therefore, it is necessary for medical industry to interfere and medicalise an illness, allowing an ill person to be more socially tolerable and less guilty for their illness, since the ‘sick role’ validates and legitimatises their illness (Gabe, Bury and Elston, 2004). This notion criticises Illich’s (1976) medical imperialism and iatrogenesis, as it teaches the individuals to take control of their illnesses, rather than the medical industries taking over their bodies (Gabe, Bury and Elston, 2004). While medicalisation is a main source of profit for the pharmaceutical companies, it can be argued that medicalisation can channel their profit into reducing human affliction and saving lives, by investing into further studies to find cures for the diseases (Williams, Gabe and Davis, 2008; WYDO, 2011).

For the rest of the blog, the case studies will be explored to demonstrate the concept of Illich’s (1976) medical imperialism and how it either supports or denies his theory.

By Kate E Stewart, Bethany L Dring and Syeda T Fahin

Leave a comment